4.12. Writing Simple Scriptsbash command lines can get to be very long, especially when pipes are used. A script is a text file that contains shell commands that may itself be executed as a command, providing an easy way to reuse complex sequences of commands. In fact, bash provides a complete programming language for use in scripts. 4.12.1. How Do I Do That?To create a script, simply place commands in a text file. For example, this script will display the ten largest files in the current directory: ls -lS | tail -n +2 | head -10 Save this file as topten. In order to run the script, you will need to set read and execute permission: $ chmod a+rx topten The script can be executed by specifying the directory and filename (or an absolute pathname): $ ./topten -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 807103 Jul 12 21:18 termcap -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 499861 Jul 17 08:08 prelink.cache -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 362031 Feb 23 08:09 services -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 97966 Jul 15 11:19 ld.so.cache -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 92794 Jul 12 12:46 Muttrc -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 83607 Mar 23 07:23 readahead.files -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 73946 Jul 13 02:23 sensors.conf -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 45083 Jul 12 18:33 php.ini -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 30460 Jul 13 20:36 jwhois.conf -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 26137 Mar 23 07:23 readahead.early.files The directory name is required because the current directory (.) is not in the list of directories normally searched for commands (called the PATH). To make your script accessible to all users, move it to the /usr/local/bin directory, which appears by default in everyone's PATH: # mv topten /usr/local/bin

4.12.1.1. Shell and environment variablesbash uses shell variables to keep track of current settings. These shell variables are private to the shell and are not passed to processes started by the shellbut they can be exported, which converts them into environment variables, which are passed to child processes. You can view all shell and environment variables using the set command: $ set

BASH=/bin/bash

BASH_ARGC=( )

BASH_ARGV=( )

BASH_LINENO=( )

BASH_SOURCE=( )

BASH_VERSINFO=([0]="3" [1]="1" [2]="17" [3]="1" [4]="release" [5]="i686-redhat-linux-gnu")

BASH_VERSION='3.1.17(1)-release'

COLORS=/etc/DIR_COLORS.xterm

COLORTERM=gnome-terminal

COLUMNS=172

CVS_RSH=ssh

DBUS_SESSION_BUS_ADDRESS=unix:abstract=/tmp/dbus-I4CWWfqvE6,guid=e202bd44a31ea8366b20151327662e00

DESKTOP_SESSION=default

DESKTOP_STARTUP_ID=

DIRSTACK=( )

DISPLAY=:0.0

EUID=503

GDMSESSION=default

GDM_XSERVER_LOCATION=local

GNOME_DESKTOP_SESSION_ID=Default

GNOME_KEYRING_SOCKET=/tmp/keyring-FJyfaw/socket

GROUPS=( )

GTK_RC_FILES=/etc/gtk/gtkrc:/home/hank/.gtkrc-1.2-gnome2

G_BROKEN_FILENAMES=1

HISTFILE=/home/hank/.bash_history

HISTFILESIZE=1000

HISTSIZE=1000

HOME=/home/hank

HOSTNAME=bluesky.fedorabook.com

HOSTTYPE=i686

IFS=$' \t\n'

INPUTRC=/etc/inputrc

KDEDIR=/usr

KDE_IS_PRELINKED=1

LANG=en_US.UTF-8

LESSOPEN='|/usr/bin/lesspipe.sh %s'

LINES=55

LOGNAME=hank

LS_COLORS='no=00:fi=00:di=00;34:ln=00;36:pi=40;33:so=00;35:bd=40;33;01:cd=40;33;01:or=01;05;37;41:mi=01;05;37;41:ex=00;32:*.cmd=00;32:*.exe=00;32:*.com=00;32:*.btm=00;32:*.bat=00;32:*.sh=00;32:*.csh=00;32:*.tar=00;31:*.tgz=00;31:*.arj=00;31:*.taz=00;31:*.lzh=00;31:*.zip=00;31:*.z=00;31:*.Z=00;31:*.gz=00;31:*.bz2=00;31:*.bz=00;31:*.tz=00;31:*.rpm=00;31:*.cpio=00;31:*.jpg=00;35:*.gif=00;35:*.bmp=00;35:*.xbm=00;35:*.xpm=00;35:*.png=00;35:*.tif=00;35:'

MACHTYPE=i686-redhat-linux-gnu

MAIL=/var/spool/mail/hank

MAILCHECK=60

OLDPWD=/usr/share/wallpapers

OPTERR=1

OPTIND=1

OSTYPE=linux-gnu

PATH=/usr/lib/qt-3.3/bin:/usr/kerberos/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/X11R6/bin:/home/hank/bin

PIPESTATUS=([0]="0" [1]="141" [2]="0")

PPID=3067

PRELINKING=yes

PRELINK_FULL_TIME_INTERVAL=14

PRELINK_NONRPM_CHECK_INTERVAL=7

PRELINK_OPTS=-mR

PROMPT_COMMAND='echo -ne "\033]0;${USER}@${HOSTNAME%%.*}:${PWD/#$HOME/~}"; echo -ne "\007"'

PS1='$ '

PS2='> '

PS4='+ '

PWD=/etc

QTDIR=/usr/lib/qt-3.3

QTINC=/usr/lib/qt-3.3/include

QTLIB=/usr/lib/qt-3.3/lib

SESSION_MANAGER=local/beige.fedorabook.com:/tmp/.ICE-unix/2621

SHELL=/bin/bash

SHELLOPTS=braceexpand:emacs:hashall:histexpand:history:interactive-comments:monitor

SHLVL=2

SSH_AGENT_PID=2659

SSH_ASKPASS=/usr/libexec/openssh/gnome-ssh-askpass

SSH_AUTH_SOCK=/tmp/ssh-dNhrfX2621/agent.2621

TERM=xterm

UID=503

USER=hank

USERNAME=hank

WINDOWID=58721388

XAUTHORITY=/home/hank/.Xauthority

_=

qt_prefix=/usr/lib/qt-3.3Many of these variables contain settings for particular programs. Some of the common variables used by many programs are shown in Table 4-16. To set a shell variable, type the variable name, an equal sign, and the value you wish to assign (all values are treated as text): $ A=red Once a variable has been assigned a value, you can use it in commands, preceded by a dollar sign: $ ls -l red ls: red: No such file or directory $ touch $A $ ls -l red -rw-r--r-- 1 hank hank 0 Jul 18 15:26 red The echo command can be used to view the value of a variable: $ echo $A red To destroy a variable, use the unset command: $ echo $A red $ unset A $ echo $A $ Finally, to make a variable accessible to processes started by the current process, use the export command: $ unset A $ TEST=blue $ echo $TEST # variable is known to the shell blue $ bash # start a child shell [hank@beige foo]$ echo $TEST # variable is not known to child [hank@beige foo]$ exit # exit back to parent shell exit $ export TEST # export the variable $ echo $TEST # value is still known to the shell blue $ bash # start a new child shell [hank@beige foo]$ echo $TEST # exported value is known to the child blue The PATH value is stored in an environment variable of the same name. Its value can be viewed like any other environment variable: $ echo $PATH /usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/X11R6/bin To add a directory to the existing directories, use $PATH on the righthand side of an assignment to insert the current value of the variable into the new value: $ PATH=$PATH:/home/hank/bin $ echo $PATH /usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/X11R6/bin:/home/hank/bin

Assuming that the topten script is saved in /home/hank/bin, you can now execute it by just typing its name: $ topten -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 807103 Jul 12 21:18 termcap -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 499861 Jul 17 08:08 prelink.cache -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 362031 Feb 23 08:09 services -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 97966 Jul 15 11:19 ld.so.cache -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 92794 Jul 12 12:46 Muttrc -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 83607 Mar 23 07:23 readahead.files -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 73946 Jul 13 02:23 sensors.conf -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 45083 Jul 12 18:33 php.ini -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 30460 Jul 13 20:36 jwhois.conf -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 26137 Mar 23 07:23 readahead.early.files Within a script, you can prompt the user using the echo command, and then use the read command to read a line from the user and place it in an environment variable: echo "Please enter your name:" read NAME echo "Hello $NAME!" Or you can collect the standard output of a command and assign it to a variable using the $( ) symbols: $ NOW=$(date) $ echo $NOW Tue Jul 18 22:25:48 EDT 2006 4.12.1.2. Special variablesThere are several special parameters, or special variables, that bash sets automatically; Table 4-17 contains a list of the most important ones. 4.12.1.3. Control structuresLike most programming languages, bash features a number of control structures to enable looping and conditional execution. The three most common control structures are listed in Table 4-18; there is also a C-style for loop that I'll discuss in the next section. The for..in control structure is great for looping over a range of values. This loop will display the status of the httpd, ftpd, and NetworkManager services: for SERVICE in httpd ftpd NetworkManager

do

/sbin/service $SERVICE status

donefor...in is even more useful when the list of values is specified as an ambiguous filename. In this script, the loop is repeated once for each file in the directory /etc/ that ends in .conf: mkdir backup

for FILE in /etc/*.conf

do

echo "Backing up the file $FILE..."

cp $FILE backup/

doneFor the if and while control structures, a control-command determines the action taken. The control-command can be any command on the system; an exit status of zero is considered TRue and any other exit status is considered false. For example, the grep command exits with a value of zero if a given pattern is found in the file(s) specified or in the standard input. When combined with an if structure, you can cause a program to take a particular action if a pattern is found. For example, this code displays the message "Helen is logged in!" if the output of who contains the word helen: if who | grep -q helen

then

echo "Helen is logged in!"

fi

The built-in command test can be used to test conditions; the exit status will be zero if the condition is TRue. The most common conditional expressions are listed in Table 4-19. So if you wanted to print "Too high!" if the value of the variable A was over 50, you would write: if test "$A" -gt 50

then

echo "Too high!"

fiThe variable expression $A is quoted in case A has a null value ("") or doesn't existin which case, if unquoted, a syntax error would occur because there would be nothing to the left of -gt. The square brackets ([]) are a synonym for test, so the previous code is more commonly written: if [ "$A" -gt 50 ]

then

echo "Too high!"

fiYou can also use test with the while control structure. This loop monitors the number of users logged in, checking every 15 seconds until the number of users is equal to or greater than 100, when the loop will exit and the following pipeline will send an email to the email alias alert: while [ "$(who | wc -l)" -lt 100 ]

do

sleep 15

done

echo "Over 100 users are now logged in!"|mail -s "Overload!" alert4.12.1.4. Integer arithmeticbash provides very limited integer arithmetic capabilities. An expression inside double parentheses (( )) is interpreted as a numeric expression; an expression inside double parentheses preceded by a dollar sign $(( )) is interpreted as a numeric expression that also returns a value.

Here's an example using a while loop that counts from 1 to 20 using integer arithmetic: A=0

while [ "$A" -lt 20 ]

do

(( A=A+1 ))

echo $A

doneThe C-style increment operators are available, so this code could be rewritten as: A=0

while [ "$A" -lt 20 ]

do

echo $(( ++A ))

doneThe expression $(( ++A )) returns the value of A after it is incremented. You could also use $(( A++ )), which returns the value of A before it is incremented: A=1

while [ "$A" -le 20 ]

do

echo $(( A++ ))

doneSince loops that count through a range of numbers are often needed, bash also supports the C-style for loop. Inside double parentheses, specify an initial expression, a conditional expression, and a per-loop expression, separated by semicolons: # Initial value of A is 1

# Keep looping as long as A<=20

# Each time you loop, increment A by 1

for ((A=1; A<=20; A++))

do

echo $A

doneNote that the conditional expression uses normal comparison symbols (<=) instead of the alphabetic options (-le) used by test.

4.12.1.5. Making your scripts available to users of other shellsSo far we have been assuming that the user is using the bash shell; if the user of another shell (such as tcsh) tries to execute one of your scripts, it will be interpreted according to the language rules of that shell and will probably fail. To make your scripts more robust, add a shebang line at the beginninga pound-sign character followed by an exclamation mark, followed by the full path of the shell to be used to interpret the script (/bin/bash): #!/bin/bash

# script to count from 1 to 20

for ((A=1; A<=20; A++))

do

echo $A

doneI also added a comment line (starting with #) after the shebang line to describe the function of the script.

4.12.1.6. An exampleHere is an example of a longer script, taking advantage of some of the scripting features in bash: #!/bin/bash

#

# number-guessing game

#

# If the user entered an argument on the command

# line, use it as the upper limit of the number

# range.

if [ "$#" -eq 1 ]

then

MAX=$1

else

MAX=100

fi

# Set up other variables

SECRET=$(( (RANDOM % MAX) + 1 )) # Random number 1-100

TRIES=0

GUESS=-1

# Display initial messages

clear

echo "Number-guessing Game"

echo "--------------------"

echo

echo "I have a secret number between 1 and $MAX."

# Loop until the user guesses the right number

while [ "$GUESS" -ne "$SECRET" ]

do

# Prompt the user and get her input

((TRIES++))

echo -n "Enter guess #$TRIES: "

read GUESS

# Display low/high messages

if [ "$GUESS" -lt "$SECRET" ]

then

echo "Too low!"

fi

if [ "$GUESS" -gt "$SECRET" ]

then

echo "Too high!"

fi

done

# Display final messages

echo

echo "You guessed it!"

echo "It took you $TRIES tries."

echoThis script could be saved as /usr/local/bin/guess-it and then made executable: # chmod a+rx /usr/local/bin/guess-it Here's a test run of the script: $ guess-it

Number-guessing Game

--------------------

I have a secret number between 1 and 100.

Enter guess #1:

50

Too low!

Enter guess #2:

75

Too low!

Enter guess #3:

83

Too low!

Enter guess #4:

92

Too high!

Enter guess #5:

87

Too high!

Enter guess #6:

85

Too low!

Enter guess #7:

86

You guessed it!

It took you 7 tries.Another test, using an alternate upper limit: $ guess-it 50

Number-guessing Game

--------------------

I have a secret number between 1 and 50.

Enter guess #1:

25

Too low!

Enter guess #2:

37

Too low!

Enter guess #3:

44

Too high!

Enter guess #4:

40

You guessed it!

It took you 4 tries.4.12.1.7. Login and initialization scriptsWhen a user logs in, the system-wide script /etc/profile and the per-user script ~/.bash_profile are both executed. This is the default /etc/profile: # /etc/profile

# System wide environment and startup programs, for login setup

# Functions and aliases go in /etc/bashrc

pathmunge ( ) {

if ! echo $PATH | /bin/egrep -q "(^|:)$1($|:)" ; then

if [ "$2" = "after" ] ; then

PATH=$PATH:$1

else

PATH=$1:$PATH

fi

fi

}

# ksh workaround

if [ -z "$EUID" -a -x /usr/bin/id ]; then

EUID=\Qid -u\Q

UID=\Qid -ru\Q

fi

# Path manipulation

if [ "$EUID" = "0" ]; then

pathmunge /sbin

pathmunge /usr/sbin

pathmunge /usr/local/sbin

fi

# No core files by default

ulimit -S -c 0 > /dev/null 2>&1

if [ -x /usr/bin/id ]; then

USER="\Qid -un\Q"

LOGNAME=$USER

MAIL="/var/spool/mail/$USER"

fi

HOSTNAME=\Q/bin/hostname\Q

HISTSIZE=1000

if [ -z "$INPUTRC" -a ! -f "$HOME/.inputrc" ]; then

INPUTRC=/etc/inputrc

fi

export PATH USER LOGNAME MAIL HOSTNAME HISTSIZE INPUTRC

for i in /etc/profile.d/*.sh ; do

if [ -r "$i" ]; then

. $i

fi

done

unset i

unset pathmungeThis script adds /sbin, /usr/sbin, and /usr/local/sbin to the PATH if the user is the root user. It then creates and exports the USER, LOGNAME, MAIL, HOSTNAME, and HISTSIZE variables, and executes any files in /etc/profile.d that end in .sh. The default ~/.bash_profile looks like this: # .bash_profile

# Get the aliases and functions

if [ -f ~/.bashrc ]; then

. ~/.bashrc

fi

# User specific environment and startup programs

PATH=$PATH:$HOME/bin

export PATHYou can edit /etc/profile to change the login process for all users, or ~/.bash_profile to change just your login process. One useful change that I make to every Fedora system I install is to comment out the if statements for path manipulation in /etc/profile so that every user has the superuser binary directories in his path: # Path manipulation

#if [ "$EUID" = "0" ]; then

pathmunge /sbin

pathmunge /usr/sbin

pathmunge /usr/local/sbin

#fi

Environment variables are inherited by child processes, so any environment variables set up during the login process are accessible to all shells (and other programs) you start. bash also supports the use of aliases, or nicknames, for commands, but since these are not inherited by child processes, they are instead placed in the file ~/.bashrc, which is executed each time a shell starts. If you log in once and then start three shells, ~/.bash_profile is executed once at login and ~/.bashrc is executed three times, once for each shell that starts. This is the default ~/.bashrc: # .bashrc

# Source global definitions

if [ -f /etc/bashrc ]; then

. /etc/bashrc

fi

# User-specific aliases and functionsAs you can see, there aren't any alias definitions in there (but you can add them). The file /etc/bashrc is invoked by this script, and it contains common aliases made available to all users: # System-wide functions and aliases

# Environment stuff goes in /etc/profile

# By default, we want this to get set.

# Even for noninteractive, nonlogin shells.

umask 022

# Are we an interactive shell?

if [ "$PS1" ]; then

case $TERM in

xterm*)

if [ -e /etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-xterm ]; then

PROMPT_COMMAND=/etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-xterm

else

PROMPT_COMMAND='echo -ne ↵

"\033]0;${USER}@${HOSTNAME%%.*}:${PWD/#$HOME/~}";

echo -ne "\007"'

fi

;;

screen)

if [ -e /etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-screen ]; then

PROMPT_COMMAND=/etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-screen

else

PROMPT_COMMAND='echo -ne "\033_${USER}@${HOSTNAME%%.*}:${PWD/#$HOME/~}"; echo -ne "\033\\"'

fi

;;

*)

[ -e /etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-default ] && PROMPT_COMMAND=/etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-default

;;

esac

# Turn on checkwinsize

shopt -s checkwinsize

[ "$PS1" = "\\s-\\v\\\$ " ] && PS1="[\u@\h \W]\\$ "

fi

if ! shopt -q login_shell ; then # We're not a login shell

# Need to redefine pathmunge, it get's undefined at the end of /etc/profile

pathmunge ( ) {

if ! echo $PATH | /bin/egrep -q "(^|:)$1($|:)" ; then

if [ "$2" = "after" ] ; then

PATH=$PATH:$1

else

PATH=$1:$PATH

fi

fi

}

for i in /etc/profile.d/*.sh; do

if [ -r "$i" ]; then

. $i

fi

done

unset i

unset pathmunge

fi

# vim:ts=4:sw=4This script sets up the umask, configures a command that will be executed before the display of each prompt (which sets the terminal-window title to show the user, host, and current directory), and then executes each of the files in /etc/profile.d that end in .sh. Packages installed on your Fedora system can include files that are placed in /etc/profile.d, providing a simple way for each package to globally add aliases or other shell configuration options. There are a few command aliases defined in these script files, including: alias l.='ls -d .* --color=tty' alias ll='ls -l --color=tty' alias ls='ls --color=tty' alias vi='vim' If you type ll at a command prompt, ls -l will be executed, due to the alias highlighted in the preceding listing: $ ll / total 138 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Jul 17 08:08 bin drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 1024 Jul 15 11:16 boot drwxr-xr-x 12 root root 3900 Jul 19 07:56 dev drwxr-xr-x 102 root root 12288 Jul 18 18:14 etc drwxr-xr-x 8 root root 4096 Jul 16 22:51 home drwxr-xr-x 11 root root 4096 Jul 17 07:58 lib drwx------ 2 root root 16384 Jun 9 19:34 lost+found drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 4096 Jul 18 18:14 media drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Jul 18 11:48 misc drwxr-xr-x 6 root root 4096 Jul 15 11:38 mnt drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Jul 18 11:48 net drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Jul 12 04:48 opt dr-xr-xr-x 126 root root 0 Jul 18 11:46 proc drwxr-x--- 9 root root 4096 Jul 18 00:18 root drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 12288 Jul 17 08:08 sbin drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 0 Jul 18 11:46 selinux drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Jul 12 04:48 srv drwxr-xr-x 11 root root 0 Jul 18 11:46 sys drwxrwxrwt 98 root root 4096 Jul 19 11:04 tmp drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 4096 Jul 14 04:17 usr drwxr-xr-x 26 root root 4096 Jul 14 04:17 var Similarly, if you type vi the shell will execute vim. You can create your own aliases using the alias command; for example, I like to use l for ls -l, sometimes use cls to clear the screen, and like to have machine report the hostname (old habits): $ alias l='ls -l

$ alias cls='clear'

$ alias machine='hostname'

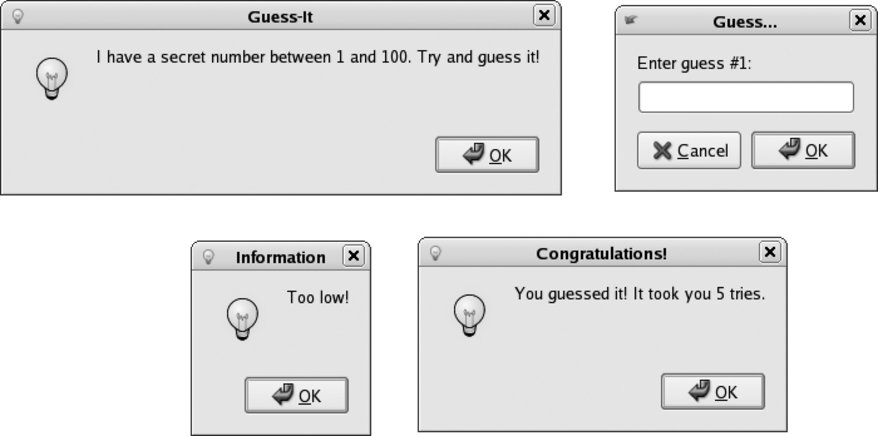

Adding the same lines to ~/.bashrc will make them available every time you start a new shell; adding them to ~/.bashrc will make them available to all users. You can see the currently defined aliases by typing alias alone as a command: $ alias alias cls='clear' alias l='ll' alias l.='ls -d .* --color=tty' alias ll='ls -l --color=tty' alias ls='ls --color=tty' alias machine='hostname' alias vi='vim' To destroy an alias, use the unalias command: $ unalias machine $ alias alias cls='clear' alias l='ll' alias l.='ls -d .* --color=tty' alias ll='ls -l --color=tty' alias ls='ls --color=tty' alias vi='vim' 4.12.2. How Does It Work?When the kernel receives a request to execute a file (and that file is executable), it uses magic number codes at the start of the file to determine how to execute it. For example, there are magic numbers for standard Executable and Linking Format (ELF) binaries and historical assembler output (a.out) binaries; the kernel will use them to set up the correct execution environment and then start the program. If the first two bytes of the file are #!, which counts as a magic number, the file is treated as a script: a pathname is read from the file starting at the third byte and continuing to the end of the first line. The shell or interpreter program identified by this pathname is executed, and the script name and all arguments are passed to the interpreter. If a file has no magic number or shebang line, the kernel will attempt to execute it as though the value of the SHELL environment variable were given on the shebang line. 4.12.3. What About...4.12.3.1. ...interacting with the user through the graphical user interface?Other scripting languages such as Perl and Python can be used to construct full-scale GUI applications, but the zenity program enables a shell script to interact with a GUI user. zenity presents a simple dialog or information box to the user. There are a number of dialog types available, including information and error boxes, text entry and editing boxes, and date-selection boxes; the type of dialog as well as the messages that appear in the dialog are configured by zenity options. Here is the number-guessing script rewritten to use zenity for the user interface: #!/bin/bash

#

# number-guessing game - GUI version

#

# If the user entered an argument on the command

# line, use it as the upper limit of the number

# range

if [ "$#" -eq 1 ]

then

MAX=$1

else

MAX=100

fi

# Set up other variables

SECRET=$(( (RANDOM % MAX) + 1 )) # Random number 1-100

TRIES=0

GUESS=-1

# Display initial messages

zenity --info --text \

"I have a secret number between 1 and $MAX. Try and guess it!" \

--title "Guess-It"

# Loop until the user guesses the right number

while [ "$GUESS" -ne "$SECRET" ]

do

# Prompt the user and get her input

((TRIES++))

GUESS=$(zenity --entry --text "Enter guess #$TRIES:" --title "Guess...")

# Display low/high messages

if [ "$GUESS" -lt "$SECRET" ]

then

zenity --info --text "Too low!"

fi

if [ "$GUESS" -gt "$SECRET" ]

then

zenity --info --text "Too high!"

fi

done

# Display final messages

zenity --info --text "You guessed it! It took you $TRIES tries." --title "Congratulations!"Figure 4-16 shows the zenity dialogs produced by this script. Obviously, this user interface is not as refined as one that could be provided by a full-featured GUI application, but it is perfectly suitable for simple interactions. Figure 4-16. zenity dialogs

4.12.4. Where Can I Learn More? |