When describing how objects can interact, we sometimes find it helpful to sketch out a scenario of specific objects and their linkages, and for that we create an object diagram. An instance, or object, looks much the same as a class in UML notation, the main differences being that

We typically provide both the name of the object and its type, separated by a colon. We underline the text to emphasize that this is an object, not a class (see Figure 10-35).

The object's type may be omitted if it's obvious from the object's name; for example, the name "student x" implies that the object in question belongs to the Student class (see Figure 10-36).

Figure 10-36: We omit the class name if it's otherwise obvious.

Alternatively, the object's name may be omitted if we want to refer to a "generic" object of a given type; such an object is known as an anonymous object. Note that we must precede the class name with a colon (:) in such a situation (see Figure 10-37).

Therefore, if we wanted to indicate that Dr. Brown, a Professor, is the advisor for three Students, we could create the object diagram shown in Figure 10-38.

To reflect that a Student by the name of Joe Blow is attending two Sections this semester, one of which is also attended by a Student named Mary Green, we could create the diagram in Figure 10-39.

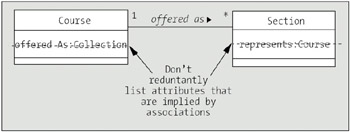

Given Figure 10-40, which shows the association "a Course is offered as a Section," we see that a Course object can be related to many different Section objects, but that any one Section object can only be related to a single Course object.

By way of review, what does it mean for two objects to be related? It means that they maintain "handles" on one another so that they can easily find one another to communicate and collaborate, a concept that we talked about in detail in Chapter 4. If we were to sketch out the attributes of the Course and Section classes based solely on the diagram in Figure 10-40, we'd need to allow for these handles as reference variables, as follows:

public class Section {

// Attributes.

private Course represents; // A "handle" on a single related Course

// object.

// etc.

}

public class Course {

// Attributes.

private Collection offeredAs; // A collection of related Section

// object "handles"

// etc.

}

So we see that the presence of an association between two classes A and B in a class diagram implies that class A potentially has an attribute declared to be either

A reference to a single instance/object of type B

A collection of references to many objects of type B

depending on the multiplicity involved, and vice versa. We say "potentially" because, when we get to the point of actually programming this application, we may or may not wish to code this relationship bidirectionally, even though at the analysis stage all associations are presumed to be bidirectional. We'll talk about the pros and cons of coding bidirectional relationships in Chapter 14.

Because the presence of an association line implies attributes as handles in both related classes, it's inappropriate to additionally list such attributes in the attribute compartment of the respective classes (see Figure 10-41).

| Note?/td> |

This is a mistake commonly made by beginners. The biggest resultant problem with doing so arises when using the code generation capability of a CASE tool: if the attribute is listed explicitly in a class's attributes compartment, and also implied by an association, it may appear in the generated code twice, as shown in the following snippet representing code that might be generated from the erroneous UML diagram shown in Figure 10-41:

public class Course {

Collection offeredAs; // by virtue of an explicit attribute

Collection offered_as; // by virtue of the association

// etc.

}

|